I first met Bill about five years ago when I decided I wanted to have a writers’ group in Baddeck. I had put up ads around town, including in the credit union, the library and the laundromat. Not long after I did so, I got an email from someone named Bill Conall, stating simply, “I am a writer and I have a clean shirt.” I remember it took me a day or two to make the connection. “Ohhhh, he must have seen the sign at the laundromat!”

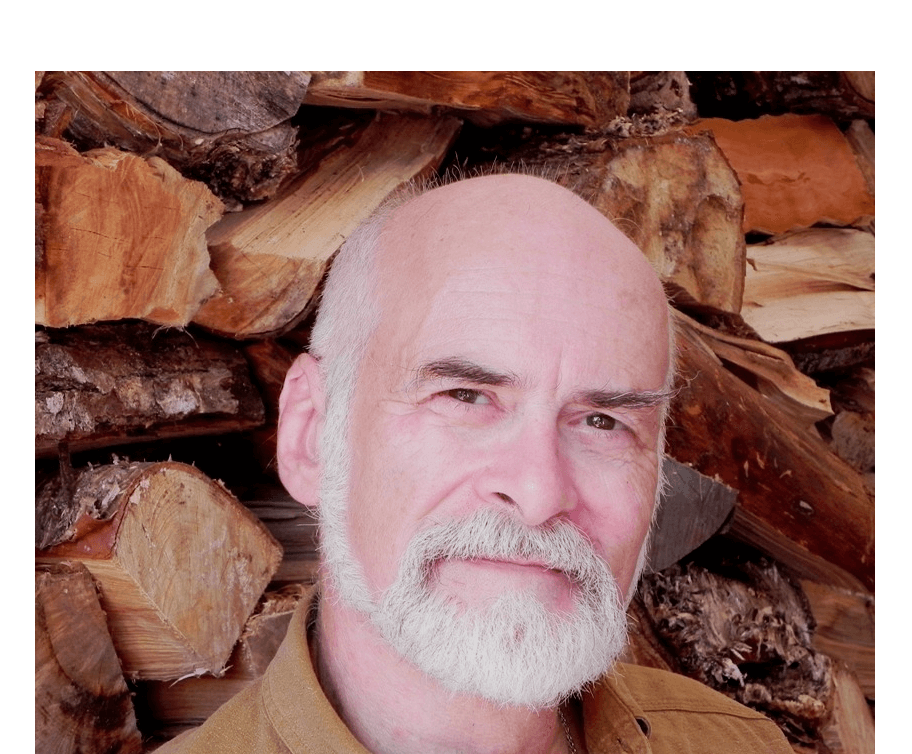

Since then, and up until just this past year when I left the writers’ group, Bill and I have been in a writers’ group together, and it has been one of the best experiences for me, as a writer. I’ve learned so much from Bill. He’s wise and knowing, he is quiet, and looks at you with a twinkle in his eye and he waits. He waits for conversations to pace themselves, for information to find its rhythm. He laughs easily. He’s lived a long and varied life, from Ontario to BC to Cape Breton, driving long-haul trucks, among other interesting occupations.

And from his natural observant, patient nature comes a gift, that of story-telling. I’ve had the luck to hear him read aloud his stories and long poems, and it brings a whole different dimension to the writing. If you have the chance to hear Bill Conall read or recite, jump at it.

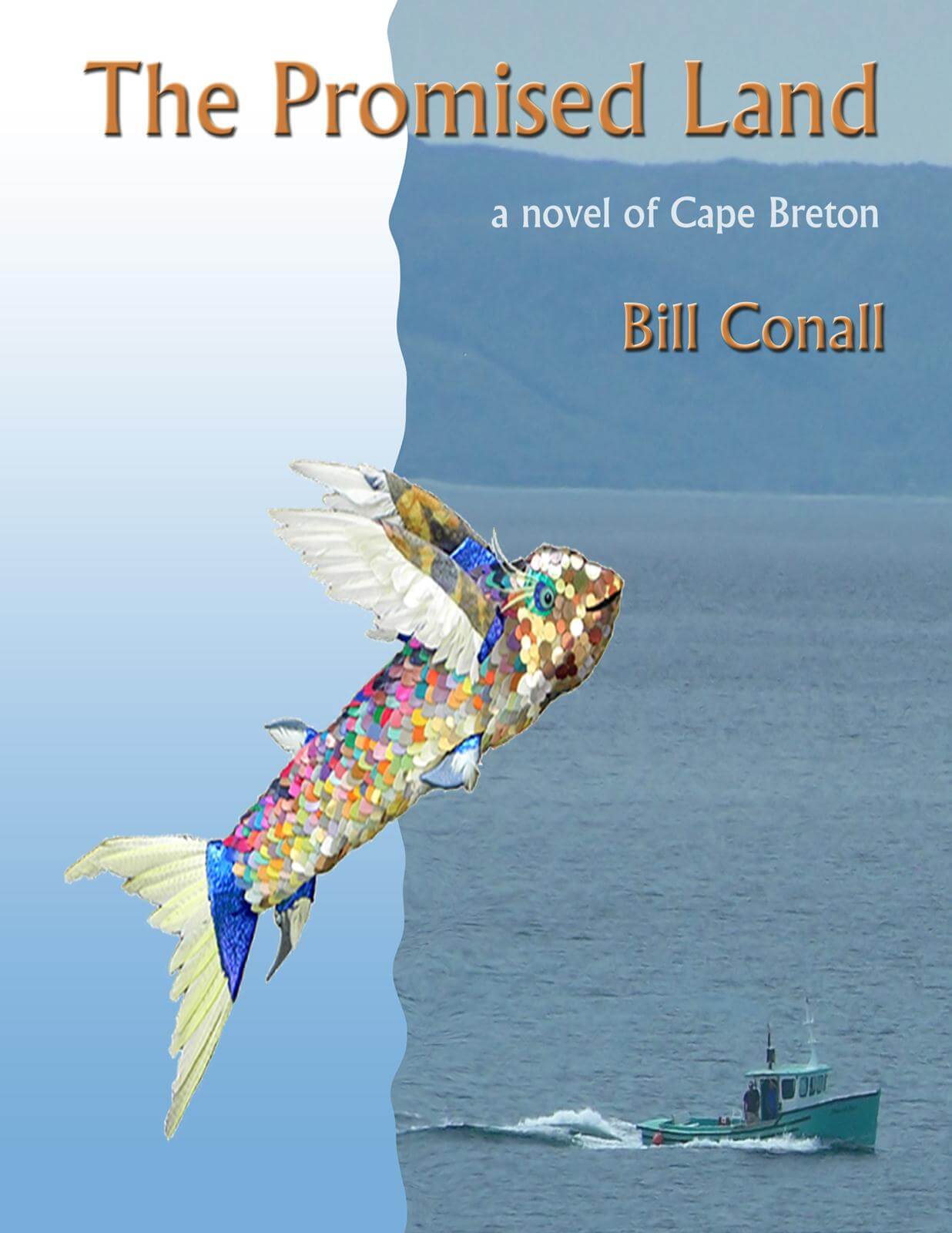

In any case, Bill is the kind of master of a craft who makes it look so easy, even simple. I imagine him like an old farmer who knows his horses so well and can guide them with just a motion, so for an outsider watching, it looks easy. But that kind of simplicity takes years of practice and work, which Bill puts in – he’s so committed to his craft. When I was in the writers’ groups with him, he would show up month after month with his work done, his notes on other people’s stories made, and discuss words, sentences, plots and ideas for hours. And he works diligently on his own writing, polishing and turning the stories again and again. It is clear that Bill Conall is in love with words, with stories, and after reading “The Promised Land,” his second novel, with Cape Breton Island.

(I remember reading early drafts of the stories in this book, before he had even found a publisher, and getting so excited, telling Bill, “I can’t wait til this is published and I can write about it on my blog!!”)

And so, it is with great pride that I present to you a Q+A with my friend, the author, Bill Conall.

(Buy The Promised Land here. Review in the Chronicle Herald here.)

When you first moved to Cape Breton, what excited you about this place? What were the things that caught your attention right away? What took time to win you over?

I was excited to be moving to where I could be closer to the land. Not goats and chickens and horse-drawn impliments, – I’m not that ambitious – but a vegetable garden, firewood, well water, wild blueberries and strawberries. The mackerel and mussels were a bonus.

We moved here on a rainy May Monday in 2007, backed the truck across the muddy yard to the house, hauled out the mattress and went to sleep. In the morning, Rosemary went to Sydney to buy a fridge. I stood on the deck looking into the box of a five-ton truck, packed to the top with everything we owned. It was a lonely, daunting moment.

But only a moment. The next sound I heard was a vehicle coming up the driveway. Our real estate agent’s husband, a lobsterman (among other things) drove into the yard with his daughter and his deck hand. “Would you like some help with that?” he asked. In just over an hour, the truck was empty. They shook hands, declined the offer of payment and drove off. Welcome to Cape Breton.

As to the last part of your question, ‘What took time to win you over?’ I can’t think of anything. I’m about as won over as I’m going to get.

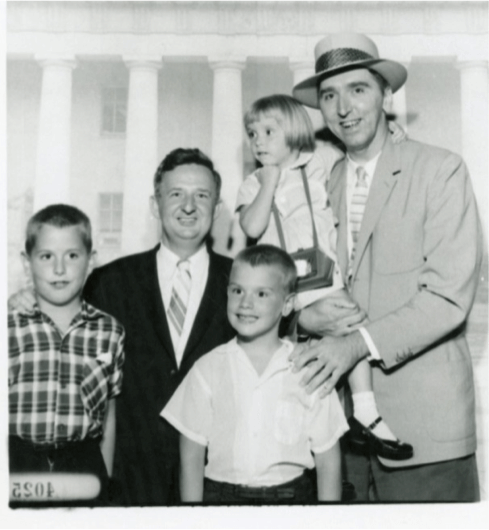

Author Bill Conall and his mighty woodpile.

Tell me about the interviews you did to prepare for the book. You mention some of them in your acknowledgements. How important were the interviews for your story?

The interviews were critical. Facts are easy to find in books or on the net, but to get a proper handle on feelings requires a live human in the equation. Facts are important, but the tone of the telling can carry even more information. A person who might be tongue-tied on paper can be eloquent with a few words and inflection. Also, a live interview provides a speaking cadence that can only be inferred in print. For example, the reading of ‘Who’s your father?’ Anyone who has spent time on the North Shore reads that phrase differently from the rest of the world.

Some interviews were undertaken specifically to prepare for the book, but many were the result of a project operated by the North Shore Gaelic Heritage Society in the summer of 2010. We collected nearly fifty hours of interviews with people ranging in age from early twenties to mid-nineties. There were people who had spent their whole life on the North Shore, people from Away, some who had gone and come back, a woman from Boston who had come up here to Granny’s farm every summer of her seventy years. I conducted some of the interviews, operated the camera for others, and did all the editing, so I was able to spend a lot of time with those people, hearing not only their stories, but also the way they told them.

There is a wake at home in the book. I wondered if this still happens in modern Cape Breton? Talk a bit about this scene, if you would.

Yes. I know of at least two in the short time I’ve been here. It used to be that all wakes were conducted at home; there were no undertakers in this part of the world until the 1950’s. The difference I noticed in my limited experience of a home wake versus a ‘commercial’ wake is that the latter seemed to focus on the ending aspect of a death while the home wake felt more like a natural continuation of a life. There was still sadness at the absence of a friend, of course, but it seemed a shorter journey from loss to fond rememberances. I spent considerable time talking with Cassandra Yonder, who is a death midwife, and who is very involved in the resurgence of home funerals. What I learned from her helped change my perceptions of death and I wanted to make it part of the story.

The scene at the Hippies Ceilidh where Seamus and Kevin have an amicable fight – this has an unreal quality to it. Is it based on a true story?

It is based on a story that was told to me as true, and I have no reason to doubt the veracity of the teller. It apparently happened on the other side of the island. At a party, a woman asked her son, “Have you had your fight yet?” “No,” he replied. “Well,” she said, “Go start something. We have to go home soon.” With that as the kernel of the story, I expanded it by adding in some observations of my own on public fighting as a pastime rather than as a domination exercise or a conflict-resolution tool.

This story feels like a love letter to your newfound home. Why was it important to you to tell a story about newcomers and locals, about the hippies of the 1970s?

Part of the reason I wanted to tell this story is because I think there are a lot of urban dwellers who have no clear idea of what life is like in a small community. I grew up in a small town where I could walk in to any of twenty or thirty houses any time and be welcomed. Nobody ever lost their car keys because they were always left in the ignition.

There is a story that demonstrates small community for me. A friend in Ontario spun out on the 401 in Toronto, ending up against the concrete median facing oncoming traffic. It was two hours before an off-duty fireman stopped, flipped on his emergency light and diverted traffic so she could turn her car around and go home. By contrast, Rosemary’s car slipped into the ditch on the way to Baddeck one day. Every vehicle on the road stopped, incuding the school bus and the garbage truck. “Do you need help? Do you need a lift to Baddeck, back home? Can I call someone for you?” That’s the kind of place I want to live.

What would you say to someone, young or old, who likes to write and who wants to tell stories about their local community? What advice would you give them?

Do it. Don’t wait for the perfect moment or stall because you can’t find the inspiring language you think your story deserves. Realize that no matter how many people may have been involved in the story, no one else has your perspective, because nobody else is you. The facts are important, so do your best to capture them as accurately as you can, but the facts are not the whole story. Write about who you were at the beginning of a chapter and how you were different at the end; write about how you felt; write about the reactions of the people around you. Write about things that you may think don’t matter, but put them down anyway. Be an eyewitness first and an editor later.

And, in the spirit of “Dreaming big”, what are your big dreams for the island, or for yourself on the island?

I am not a member of the bigger/better/farther/faster fraternity. There will be change, of course, but my wish is that whatever changes come, we never lose sight of what makes this such a special community. I hope that we continue to care for each other; to stop and offer help if we see somebody in the ditch; that we never lose track of how lucky we are to live in such a beautiful place.

You can purchase “The Promised Land” here.

This Q+A with Bill is part of an ongoing series of interviews with people associated with Cape Breton in some way – mostly young people, but not necessarily. The complete list of interviews is here.

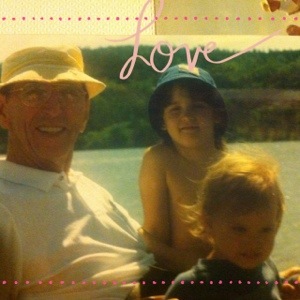

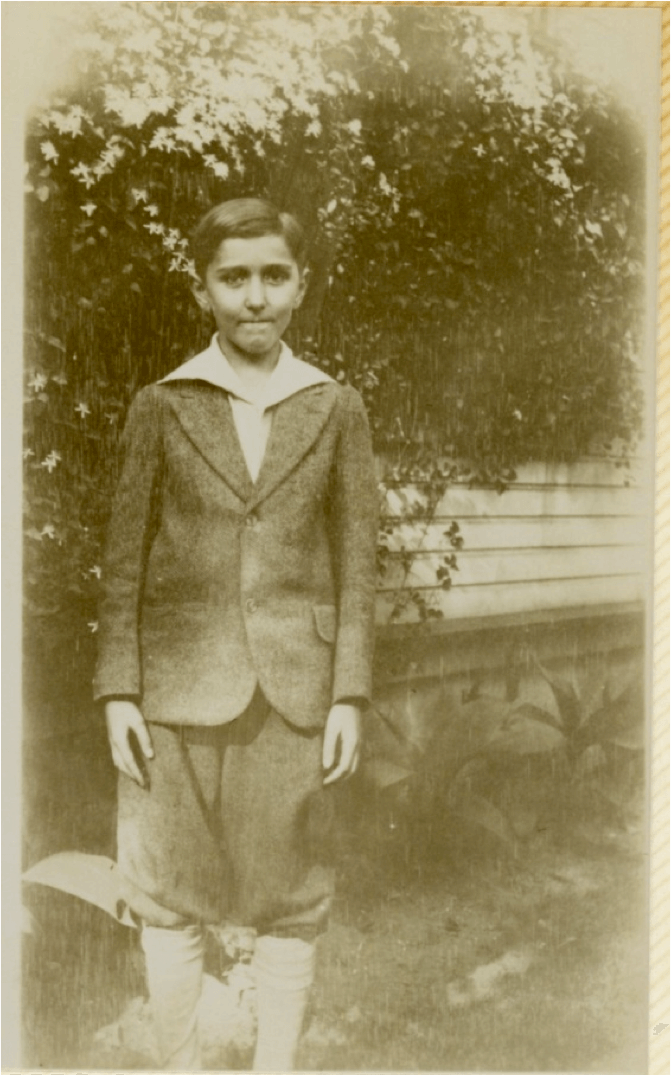

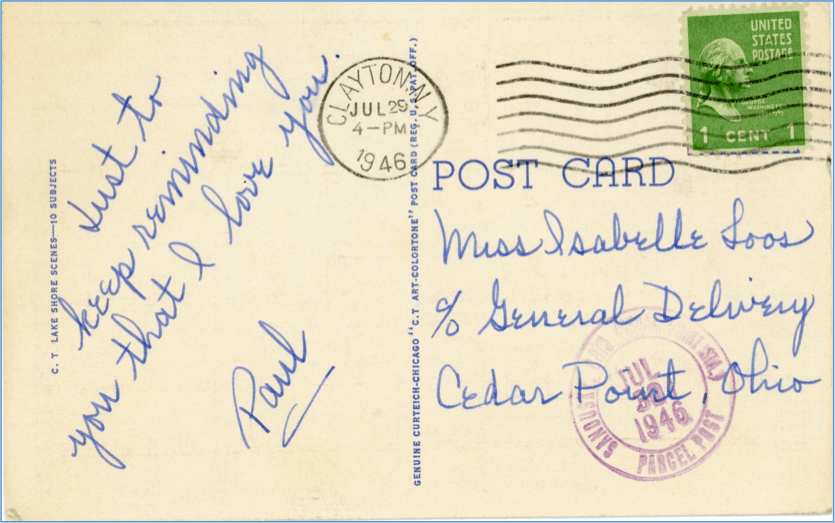

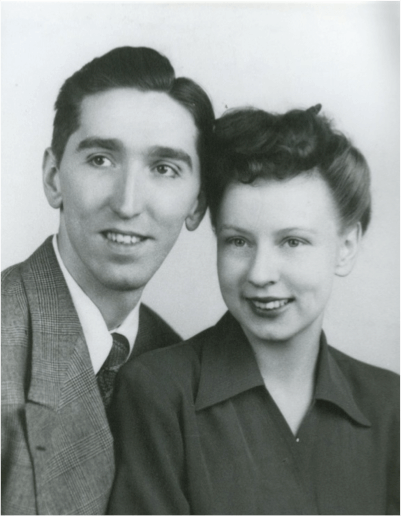

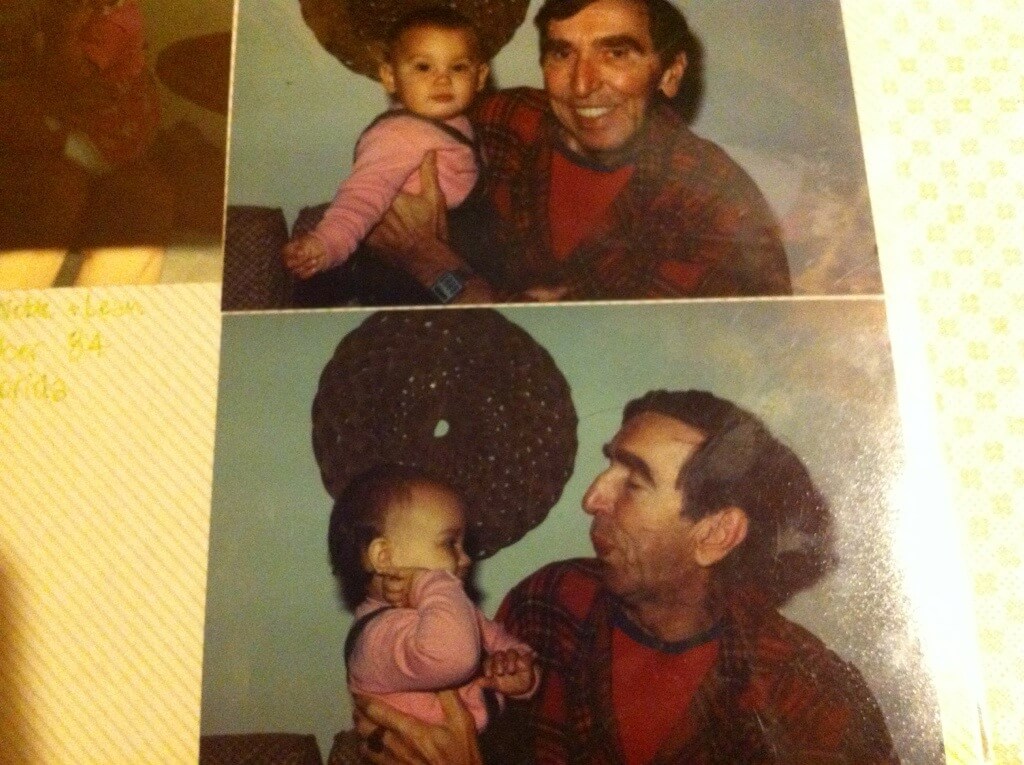

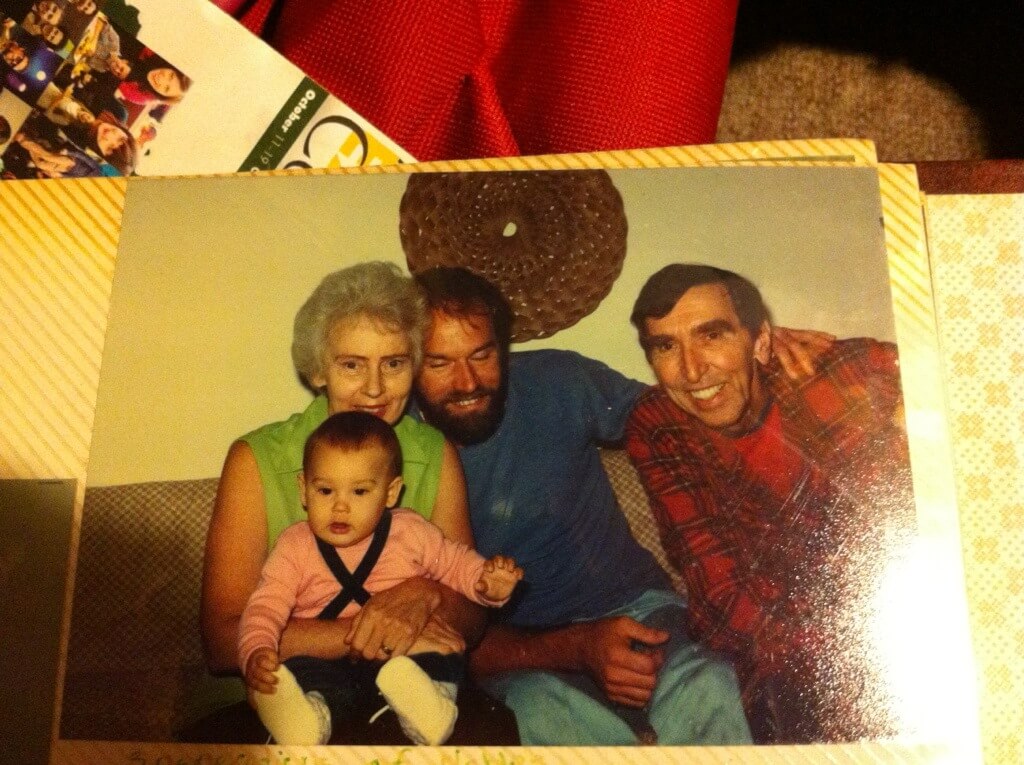

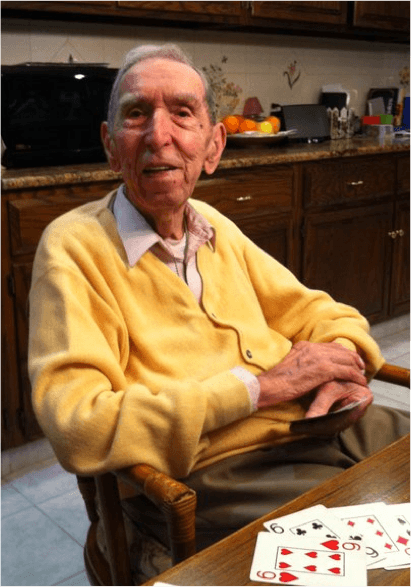

My Grandpa, Paul Noble, passed away last month.

My Grandpa, Paul Noble, passed away last month.