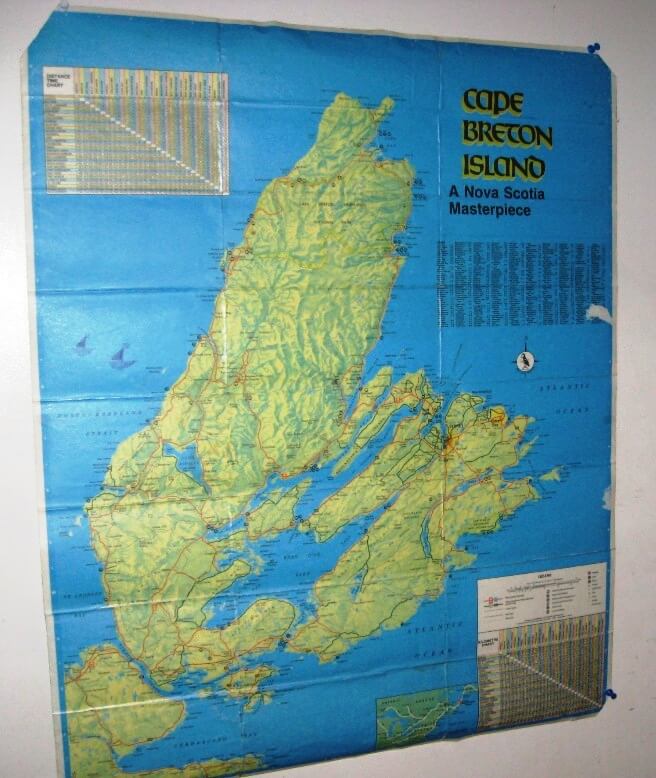

Morwenna Hancock and her family moved to Cape Breton from England, intending to stay only a short while on their way British Columbia, but liked it so much they are now putting down roots here. A mutual friend referred Morwenna to me, knowing that I’d be interested in her insight on life in Cape Breton. I went to her home in North Sydney on February 3 to meet her and find out more about her family’s reasons for staying in Cape Breton.

The Hancocks live in a medium-sized home in a quiet neighbourhood near a local school. Morwenna, a pretty young woman with pixie-cut brown hair and friendly eyes, welcomed me in and made me a cup of tea, while her elder daughter Rhiannon, five years old, played a Curious George program on the laptop on the floor nearby. Imogen, 2 and ½ years old, was down for her afternoon nap and husband Jan was at work. The fireplace crackled cozily and the two cats came in and out of the room to check me out while we sipped our tea and talked.

Before Morwenna and Jan had even met, at home in England, he had spent time here in Canada and liked it so much that he hoped one day to live here, in BC specifically. Then he met Morwenna and she wasn’t so sure about leaving England, but when they spent their honeymoon in BC, she was convinced. “I went – ‘yeah, I could see myself living here’.”

A year later, in 2006, they went back to BC and bought a house in Nelson. But they still had to obtain Permanent Residency visas in order to move there. Back in England, they found out that if one of them got a job offer in Canada, and worked in the country on a work visa, that this would help to fast-track their Permanent Residency applications. At an emigration fair, they found an Canadian company which could help them do the paperwork and help to find job postings. The Hancocks asked for jobs postings from BC since they already owned a house there, but were open to considering other locales, especially those on the East Coast, which, compared to BC, didn’t have as much competition in the job market.

Morwenna explains how they initially heard of North Sydney: “So one day I got a call and the company said ‘we found two possibilities, one is in this town called Fort McMurray, and one is in this town called North Sydney’. So… I googled Fort McMurray, and I googled North Sydney, and I decided it would be… North Sydney!”

She interviewed and got the job, and then she, Jan and Rhiannon moved across the pond. Morwenna went to work as an executive assistant for a local businessman, and Jan stayed home as a housedad with Rhiannon. Within six months they got their Permanent Residency visas. Now they could go out west as planned, to the home they still owned in Nelson and were renting to tenants in their own absence. But then Jan, who has a PhD in Political Science, was offered work at Cape Breton University, and their second child was born. The home in BC needed much work done to it, whereas the home they owned in North Sydney was in good shape. So in 2010 they sold the home in BC, and decided to stay in Cape Breton.

I asked Morwenna, “What sorts of things contributed to your decision to stay here?”

Morwenna: “The way of life here. We weren’t looking for a big city. We wanted to get back in touch with a more traditional way of life, and a deeper sense of community. That was one of the biggest things. We had lived in a couple of different places in England and never felt part of … the community. All our neighbours here are so sweet. They’ve helped us out when we’ve had problems, they keep an eye out on the girls when they’re playing outside, in between all the gardens. People in England used to be like that, but it’s changed so much. It’s so much more introverted now.”

She continues, “And we’d made a good bunch of friends, and started to feel settled. And honestly, the job market here is better! This is at least a university town, whereas in Nelson there was no big university. So there was nothing for my husband out there. And I had no reason to see why I would do any better in my line of work there than here.”

So they stayed. And they feel part of a vibrant community. On the subject of whether or not she feels her family is welcomed here, or if they’re seen as “come from away’s”, Morwenna says of a group of mothers who get together to have a weekly playdate, that “it’s a real melting pot. There are a couple of people in the group whose family has been here for generations going back, you know, they’re born and raised here, they’re “thoroughbred” locals. And a couple of my friends lived here til they were 18, moved away, then moved back when they had children. And then there’s a few of us who have never lived here. And it all kind of gets forgotten, it all comes out in the wash. We’re all the same underneath.”

“However, in my professional life, it’s noticed that I’m ‘from away’. It’s not always a bad thing, you know, but it comes out… like when I try to do things and people will say sort of ‘well… don’t you know how things are done here?’ and I’m like ‘no, no I don’t know!’” (Laughs.) “ I don’t know the local businesses, or I don’t know all the ins and outs and the personalities, and that you can’t get this company to work with that company. The things that only locals know.”

A local might also have an advantage when it comes to childcare. Where a local mother would know “the 16-year-old down the street,” Morwenna doesn’t. But she and a friend who is also “from away” have teamed up to trade baby-sitting services. “Most locals have all this family here, so they don’t need to worry as much about finding a babysitter,” she says.

We get to talking about some of the challenges of living here. While she loves her adopted home, Morwenna says, “In the winter, it’s difficult to find new things to do. I mean, we don’t let winter stop us. There’s huge amounts of hiking trails, there’s Ski Ben Eoin, there’s parks and things galore. But if you want a family day out with a little café, an indoor sort of thing, a package… it doesn’t exist. Even just the summer after Imogen was born, my family came over from England. We set out in the morning to go to the Highland Village, but we didn’t get there until around noon, so we went looking for somewhere to eat. And… the Highland Village doesn’t have anything. We knew we could eat at the hotel next door but that day it had a wedding, and it was shut. So we said ‘well, where can we eat?’ and [the Highland Village staff] said “well, there’s Beaver Cove – half hour, forty five minute drive away – or Baddeck. [Another 45 min drive in another direction.] And we were like, ‘that’s it?’”And this was in August. We’re not talking middle of winter. I mean, I know there’s a small population there, but it just seemed… crazy.”

Morwenna sees other opportunities, too. She mentioned an idea she’d heard about of building an aquarium in downtown Sydney, near the Cruise Ship Pavilion, something that could be open year-round and that would attract locals as well as tourists. She also mentioned that she’d love to see a children’s playplace open during the day, for a change of scene for her girls. (There is one close by but it is only open for birthday parties.)

She admits, though, that bringing business ideas like these to life is “hard work. And there’s this contradiction that I find here. The people themselves, individually, are incredibly hard-working. But at the same time there’s almost this whole collective attitude of “well… but no-one’s given us anything here!” And, you know what, no! And, they’re not gonna! We need to think ourselves out of this problem. We need to decide what the community needs. We need to ask questions – like Steve Sutherland and his Leaders series, we need to ask – what are we gonna do? What are we doing, going forward? And if you multiply that [kind of resourcefulness and questioning] out, you probably can get somewhere. But you need that collective psyche to stop going – ‘the mines are shut, the steel plant’s shut, well… what are we gonna do [besides take handouts]?’ Cause it’s almost this… state of shock, that the culture is in.”

Morwenna saw this happen in the village n England where she is from, Huntley, which used to be an industrial area. And the people of Nelson, BC, told her the same thing happened with the demise of their forestry industry. In both cases she says the communities had to go through a phase of shock before they could collectively help decide the future of the area, and move forward. She thinks Cape Breton is experiencing this state of shock, but hopes things are moving forward. She sees the money that Cape Bretoners earn out West as a possible catalyst for change.

“I wonder if there will be a tipping point, where people are bringing in enough money from out West, to kind of kickstart things here? Bring in money earned out west but stop it going back out west. I don’t know how much we’re seeing the real benefit of that money here yet! We should be trying to plow that money back in to … local business. You know, use your money here. Go out West and make a pot, and then kickstart something here.

“But I think that [what keeps people from doing that is] then you have to give up your life out West to be here and just do that hard slog [of building a business]. But – there’s a bigger payoff down the road, for society here.”

***

If you’d like to be featured on the Dream Big blog, or if you know someone who I should speak to, get in touch!